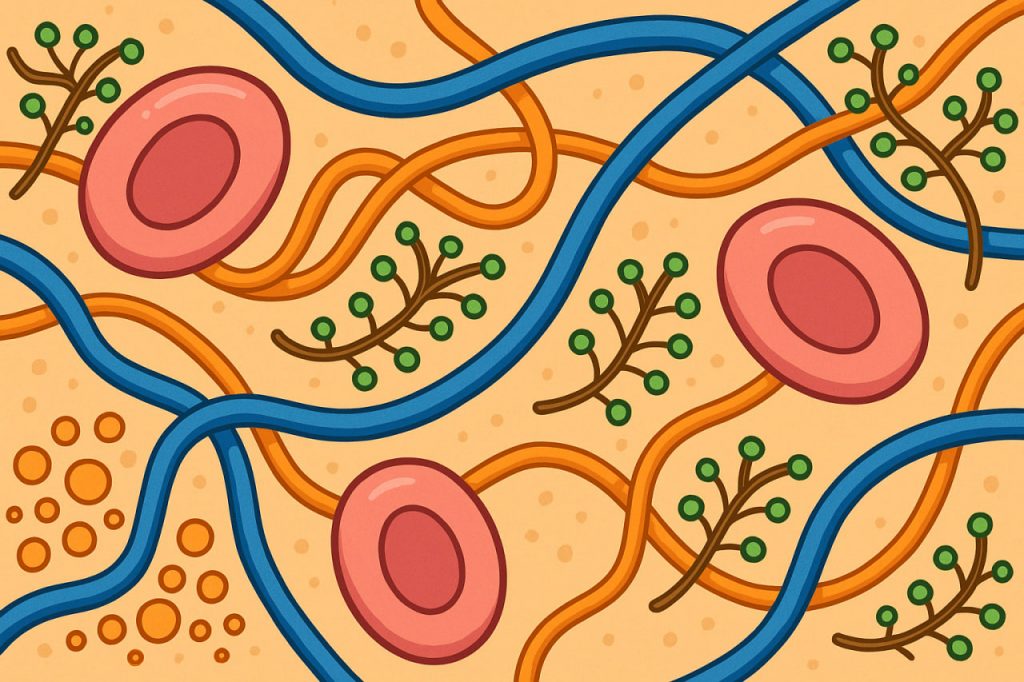

The extracellular matrix (ECM) is a complex structural network that surrounds and supports the cells in all tissues of the human body. Although often described as the “scaffolding” of tissues, the ECM is far more than a passive framework. It regulates cell communication, tissue repair, nutrient transport, mechanical strength, and even gene expression. Without the extracellular matrix, cells would lose their shape, tissues would collapse, and vital biological processes would fail. Scientists consider the ECM a dynamic, living environment that constantly remodels itself in response to stress, aging, disease, and cellular activity.

The ECM is composed of proteins, sugars, minerals, and water. Collagen fibers provide strength; elastin gives flexibility; glycoproteins guide cell attachment; and proteoglycans regulate hydration and shock absorption. Together, these molecules create a three-dimensional microenvironment that determines how cells behave. Healthy tissue depends on a balanced ECM, but when the matrix becomes damaged or overly rigid, many diseases can develop — from fibrosis to arthritis to cardiovascular problems.

What the Extracellular Matrix Does

The ECM performs multiple essential functions that go far beyond structural support. It stores biochemical signals, coordinates immune responses, and guides tissue growth. According to cellular biologist Dr. Helena Ward:

“The extracellular matrix is not just a framework —

it is an active communication platform that tells cells how to live, divide, and repair.”

The ECM acts as a bridge between physical forces and cellular behavior, helping tissues maintain stability while adapting to change.

Key Components of the ECM

The extracellular matrix consists of several main molecular groups:

- Collagen — provides tensile strength and durability

- Elastin — allows tissues to stretch and return to shape

- Proteoglycans — regulate hydration and absorb mechanical shock

- Glycoproteins (e.g., fibronectin, laminin) — help cells attach to their environment

- Minerals — especially important in bone, where calcium phosphate hardens the ECM

- Interstitial fluid — transports nutrients and removes waste

Each tissue has a distinct ECM composition depending on its function. For example, bone contains rigid mineralized ECM, while skin has elastic ECM designed to stretch and resist damage.

How Cells Communicate With the Matrix

Cells constantly interact with the ECM through specialized receptors. These receptors sense:

- mechanical stress

- chemical signals

- tissue damage

- inflammation

- external forces

Through these interactions, the ECM regulates cell movement, division, and specialization. Stem cells, for example, change their behavior depending on the stiffness or softness of the matrix surrounding them.

ECM and Tissue Repair

When tissues are injured, the extracellular matrix plays a central role in healing. It guides immune cells to the wound, supports temporary scaffolding for repair, and helps organize new tissue formation. If this process becomes excessive, however, it can lead to fibrosis — the buildup of thick, stiff ECM that disrupts normal function.

As regenerative medicine researcher Dr. Marcus Levin explains:

“Every step of healing depends on the ECM —

but imbalance between repair and scarring determines recovery quality.”

Understanding these mechanisms is crucial for developing therapies to reduce fibrosis and improve tissue regeneration.

ECM Changes With Aging and Disease

The extracellular matrix is highly dynamic, but its properties change over time:

- collagen fibers accumulate cross-links and become rigid

- elastin breaks down, reducing tissue flexibility

- hydration decreases, affecting nutrient transport

- tissue repair becomes slower and less efficient

These changes contribute to visible signs of aging as well as deeper biological changes in organs and joints. Chronic diseases often involve ECM dysfunction, including arthritis, heart disease, lung fibrosis, and tumor progression.

Why the ECM Is Important for Modern Science

Researchers study the ECM to develop:

- artificial tissues and organs

- improved wound-healing materials

- cancer therapies targeting the tumor microenvironment

- regenerative medicine techniques

- biomaterials that mimic natural tissue structures

The ECM is becoming a central topic across biology, medicine, and bioengineering, offering new possibilities for treating complex diseases.

Interesting Facts

- Collagen is the most abundant protein in the human body — primarily found in the ECM.

- The ECM can transmit mechanical forces that influence gene expression.

- Each organ has a unique ECM “signature,” like a biochemical fingerprint.

- Cancer cells often remodel the ECM to help themselves spread.

- Artificial ECM scaffolds are used to grow lab-made tissues.

Glossary

- Collagen — a structural protein that gives tissues strength.

- Proteoglycan — a molecule that regulates hydration and shock absorption.

- Fibronectin — a glycoprotein that helps cells attach to the ECM.

- Fibrosis — excessive accumulation of ECM that stiffens tissue.

- Microenvironment — the local biochemical and physical environment surrounding cells.