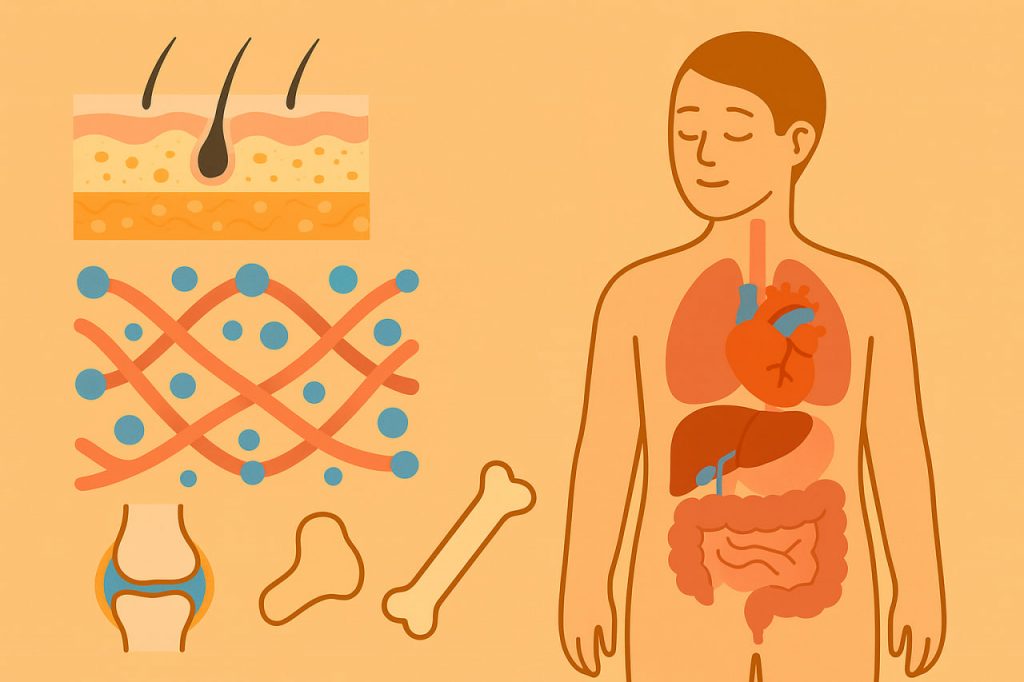

Collagen is the most abundant structural protein in the human body, comprising nearly 30% of total protein content. It forms a vital part of connective tissues, including skin, cartilage, bones, tendons, and blood vessels. Collagen provides strength, elasticity, and structural integrity to tissues, enabling them to resist stretching, tearing, and degradation. Its presence is essential not only for mechanical function but also for cellular communication, wound healing, and regeneration. The human body synthesizes collagen naturally, but this process slows with age and is influenced by nutrition, hormones, and environmental factors.

Types and Distribution of Collagen

There are at least 28 known types of collagen, but five are most prominent in the body. Type I collagen is the strongest and most abundant, found in skin, bones, tendons, and ligaments. Type II collagen is primarily located in cartilage and is crucial for joint function. Type III supports organs and blood vessels, while Type IV is found in basal membranes, and Type V contributes to cell surfaces and hair.

Each type of collagen forms specific fiber structures adapted to tissue needs—some form dense, rope-like fibers, while others create mesh-like networks. This structural variety explains collagen’s role across different organ systems.

Collagen Synthesis and Degradation

Collagen synthesis involves the assembly of amino acids, especially glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline, into a triple helix structure. This process requires adequate levels of vitamin C, which acts as a cofactor in collagen cross-linking. After synthesis, collagen fibers are secreted into the extracellular space, where they are organized into networks by fibroblasts.

With age or due to oxidative stress, collagen production decreases and collagenase enzymes break down existing fibers. This leads to common signs of aging such as wrinkles, joint stiffness, and loss of elasticity in tissues.

Function in Skin and Soft Tissues

In the dermis, collagen maintains skin firmness and hydration by forming a supportive matrix that binds water and resists mechanical deformation. Loss of collagen in the skin contributes to thinning, sagging, and increased susceptibility to injury. Collagen also plays a role in wound healing by providing a scaffold for new tissue growth.

In muscles and organs, collagen maintains internal structure and prevents excessive expansion. Its network supports cell adhesion and migration, facilitating tissue repair and regeneration.

Role in Joints, Bones, and Cartilage

Cartilage, especially in weight-bearing joints, relies on Type II collagen for shock absorption and smooth movement. Collagen fibers form a resilient framework that allows cartilage to resist compression and wear. In bones, Type I collagen acts as a scaffold for calcium phosphate deposition, contributing to bone hardness and flexibility.

Deficiency or degradation of collagen in these tissues contributes to osteoporosis, osteoarthritis, and reduced mobility. Maintaining adequate collagen is crucial for musculoskeletal health throughout life.

Factors Affecting Collagen Levels

Several factors influence collagen metabolism. These include age, ultraviolet radiation, smoking, chronic inflammation, and poor nutrition. Diets lacking in protein, vitamin C, zinc, and copper can impair collagen synthesis. At the same time, exposure to free radicals and glycation—sugar-induced damage to collagen—accelerates its breakdown.

While the body produces collagen naturally, external support through lifestyle and diet is essential to preserve its function and integrity over time.

Conclusion

Collagen is indispensable for maintaining the body’s structure, elasticity, and tissue resilience. Its presence is foundational to skin, bones, joints, blood vessels, and internal organs. As collagen production declines with age, preserving it becomes key to maintaining mobility, strength, and appearance. A combination of balanced nutrition, sun protection, and avoiding inflammatory triggers can help sustain healthy collagen levels throughout life.

Glossary

- Collagen — the main structural protein in connective tissues, providing strength and elasticity.

- Connective tissue — biological tissue that supports, binds, or separates other tissues and organs.

- Fibroblasts — cells responsible for producing and maintaining the extracellular matrix and collagen.

- Triple helix — the molecular structure formed by three collagen chains.

- Glycation — a process where sugars bind to proteins, impairing their function.

- Hydroxyproline — a collagen-specific amino acid important for structural stability.

- Collagenase — an enzyme that breaks down collagen fibers.

- Extracellular matrix — the network outside cells that provides structural support.